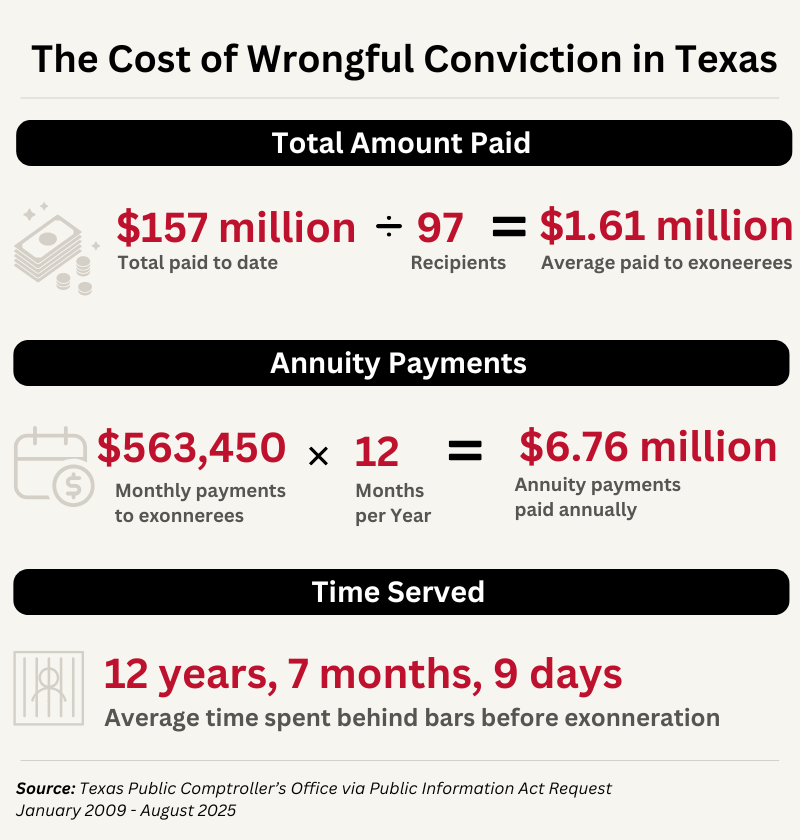

Since 2009, Texas has paid a total of $156,678,037.45 to 97 individuals who were wrongfully convicted, according to state records requested by Michael & Associates, a criminal defense law firm based in Austin, Texas, under the state’s Public Information Act.

This breaks down to over $103 million in lump sum payments, and an additional $563,449.94 per month in annuity payments, according to 2025 state records.

That breaks down to an average payment of $1,615,237.50 per individual.

These totals are expected to increase considerably. In 2024, another 26 Texans were cleared of crimes ranging from drug charges to child abuse and murder, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. However, it can take months or even years for them to receive compensation.

Key Takeaways

- On October 16, Texas is scheduled to execute Robert Roberson on a capital murder conviction, even as the state refuses to acknowledge evidence that no crime occurred, raising questions about whether officials are concerned about the cost of compensation.

- Of the 96 exonerees who receive compensation from the state, 58 are Black, 27 are White, 10 are Hispanic, and one is Native American

- Ben Spencer, who was exonerated in 2024 after spending almost 34 years behind bars, received the highest lump-sum payment at $2.7 million.

Total Payments: $156,678,037.45

As of July 1, 2025, records show the state has paid $156,678,037.45 in compensation to individuals who were wrongfully convicted since 2009.

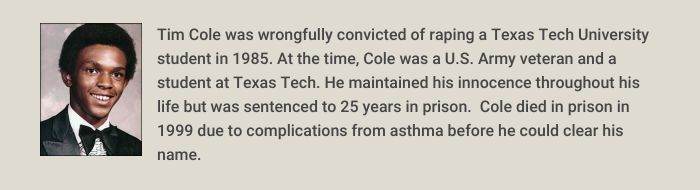

The compensation is due to the Tim Cole Act, a law enacted in 2009 that is named after a former student at Texas Tech University. Cole died in prison in 1999 while serving a 25-year rape sentence. Almost a decade later, Cole was posthumously exonerated by DNA evidence.

This law requires the state to pay exonerees $80,000 per year of wrongful imprisonment, plus a monthly annuity payment to provide financial security for the future. They’re also eligible for an additional $25,000 per year for every year they were wrongfully required to register as a sex offender or were on parole or other restrictive conditions after release from prison.

At Michael & Associates, we believe every defendant is entitled to the best possible defense. As part of our commitment, we have compiled data and statistics on exonerations in Texas, using records from the Texas State Comptroller’s Office to examine the impact of wrongful convictions.

Lump-sum payments: $103,173,486.80

As of July 1, 2025, the state has paid $103,173,486.80 in lump-sum payments.

Is that enough to compensate for the years they’ve lost? It’s tough to say.

Only 31% of the Texas prisons are fully air-conditioned, and a 2022 study found that an average of 14 inmates a year die due to heat exposure. At least one inmate gave birth while incarcerated.

Some have been behind bars for decades, and when they’re finally released after the lengthy exoneration process, they are overwhelmed by new technology and find their career skills are outdated.

“Some men and women are incarcerated so long that they’ve lost loved ones while incarcerated and have no support or family structure intact to return to,” said Jessica Weinstock Paredes of the National Registry of Exonerees at the University of Michigan.

Monthly Annuity Payments: $6,761,519.30 per year

In addition to the lump sum payments, the state also pays eligible exonerees a monthly annuity. Records show that those payments total $563,459.94 per month.

To calculate the annuity payments, the comptroller’s office says actuaries from the Social Security Administration estimate each exoneree’s life expectancy. The monthly payment is based on the lump sum payment they received, plus 5% compounded interest, divided by the expected lifespan of each person.

The payments end if an exoneree dies or is convicted of a felony. Though seven have passed away since their exonerations, data from the state only lists four as deceased. This includes Cole (who was exonerated posthumously), Steven Chaney, Lenora Chaney, and Raymond Jackson. Three more – Billy James Smith, Johnnie Lindsey, and James Lee Woodard – have also died since their exonerations.

Two other exonerees, Geary Wilkins and Joey Ray Carabajal, have subsequently been convicted of felonies and are no longer eligible for compensation.

Years Incarcerated: 1,210 years, 5 months, 28 days

Those receiving lump-sum payments spent as few as zero days in prison (Lenora Chaney was paid a lump-sum payment on behalf of her husband, Steven Chaney, who is deceased) or as long as 33 years, 11 months, and 16 days (Benjamin Spencer).

Spencer received the highest lump sum payment – $2.7 million. His case was a complicated one. In 1987, he was convicted of murder by a jury in Dallas County in connection with the death of a clothing company executive. However, a post-conviction investigation raised new questions about his guilt, and he was given a new trial, where jurors convicted him of aggravated robbery instead. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Spencer remained in prison for almost 34 years, proclaiming his innocence. In 2021, Dallas County’s Conviction Integrity Unit, led by District Attorney John Creuzot, became involved in the case.

Spencer was exonerated on August 29, 2024. However, records currently list him as ineligible for a monthly annuity payment.

Spending such a long time behind bars can make re-entering society extremely difficult.

“A lot of formerly incarcerated people experience a form of post-traumatic stress disorder upon their release,” says Daniel Medwed, a professor at Northwestern University and author of Barred: Why the Innocent Can’t Get Out of Prison. “And that can be compounded for an exoneree who not only lived through the day-to-day indignities and dangers of prison but also did so as an innocent person whose pleas for justice were often ignored or disbelieved.”

Wrongful Convictions and the Robert Roberson Case

The high number of wrongful convictions in Texas is particularly relevant as the state is poised to execute Robert Roberson on Oct. 16, 2025, despite questions about whether Roberson is actually guilty of a crime.

Roberson, who is autistic, was convicted of capital murder in Dallas County for the 2002 death of his 2-year-old daughter, Nikki. His conviction and death sentence were based on a now-discredited "Shaken Baby Syndrome" (SBS) diagnosis. Roberson’s defense argues that Nikki’s death was caused by viral and bacterial pneumonia, and Mr. Robertson maintains his innocence.

The Roberson case has drawn national attention. People fighting to halt Mr. Roberson's execution include bestselling author John Grisham and TV host Dr. Phil McGraw, both of whom have testified on Roberson’s behalf, convinced of his innocence. Additionally, the former lead detective on the case, Brian Wharton, who is now a minister, has also reversed his stance and is advocating for Roberson's life to be spared.

The state's refusal to acknowledge the new evidence in the Roberson case raises questions about whether state officials are worried about the cost of compensating him. If Mr. Robertson is ultimately exonerated, he would be eligible for a lump sum payment of approximately $1.7 million.

“At this point, we are laser-focused on trying to stop a wrongful execution," said Gretchen Sween, an attorney fighting to stop Mr. Roberson's scheduled execution. "It would be the depth of moral depravity if the reason why state actors have refused to even acknowledge the mountain of new evidence demonstrating that no crime occurred is because of some fear of having to compensate Robert one day.

Roberson would be the first person to be executed because of this now-discredited theory. In fact, one of Texas’s most recent exonerees, Andrew Wayne Roark, had his conviction overturned by an appeals court in November 2024 over the same debunked shaken baby syndrome theory used in Roberson’s conviction.

At least 200 people who spent time on death row have been exonerated since 1973, according to data from the Death Penalty Information Center. At least 18 of these people were convicted and sentenced to death in Texas.

Roberson would not be the first potentially innocent person to be executed in Texas.

According to information from the Death Penalty Information Center, six executions – those of Cameron Todd Willingham, Carlos DeLuna, Ruben Cantu, Gary Graham (Shaka Sankofa), Larry Swearingen, and Ivan Cantu – were carried out despite “strong evidence of innocence,” including new evidence that was uncovered after the inmate was put to death.

Racial Breakdown

More than half of those who were wrongfully convicted were Black:

Of the 96 exonerees, 58 were Black, 27 were White, 10 were Hispanic, and one was Native American. This is consistent with national numbers. Research by the National Registry of Exonerations shows that more than half of all exonerees nationwide between 1989 and 2022 are Black, even though Black people account for roughly 13.6% of the U.S. population.

Thousands More Cases Pending

The Innocence Project of Texas estimates that 3,000 to 9,000 individuals are currently incarcerated in Texas prisons due to wrongful convictions.

Texas has a high number of exonerations, with 474 recorded by the National Registry of Exonerations since 1989, and 26 exonerations in the most recent year, 2024, often due to official misconduct or drug-related cases that were later determined to be non-crime offenses.

According to data from the National Registry of Exonerations, Texas has the second-highest number of exonerations in the U.S., with 486. Only Illinois has more, with 555.

Is This a Fair Price for Years Lost?

Michelle Moore, one of the founding members of Dallas County’s conviction integrity unit, cited widespread health and dental problems among exonerees due to poor health care for Texas prison inmates.

Moore said inmates got primary care, but there was no follow-up treatment.

Johnnie Lindsey, who spent almost 18 years in prison before he was exonerated, developed cancer while incarcerated. While he was given chemotherapy, Moore said that was the end of his treatment. He did not get routine screenings to ensure that the cancer didn’t return.

Lindsey received $1,820,000 in state compensation and a monthly annuity of $11,300. He died of liver cancer in January 2018.

At least one female exoneree in Travis County, Rosa Estela Jimenez, missed watching her children grow up.

When she was convicted, Jimenez was seven months pregnant and had a one-year-old child. When she gave birth to a son after her conviction, she was only allowed to hold him for a total of five hours before he was placed in the state foster care system. By the time Ms. Jimenez was exonerated, she was already suffering from end-stage kidney failure, which doctors say is most likely the result of overuse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen during her time behind bars.

Despite situations like Ms. Jimenez’s, “Texas does much better in this area than most states,” says Jeffrey Gutman, a professor at George Washington University Law School who studies exoneree compensation in the U.S.

Larry Charles Fuller was the first exoneree to receive a lump-sum payment under the new law on Nov. 12, 2008. He spent almost 20 years in jail before he was released from prison on October 31, 2006.

More than One-Third of Wrongful Convictions Were in Dallas County

The five largest counties in Texas account for 65 of 96 overturned convictions.

Though there are 97 names on the list of payments, there are technically only 95 exonerees. One inmate, Dejuan Anthony Jordan, was exonerated on two separate charges of failure to register as a sex offender and thus was entitled to two lump-sum payments. The final recipient was Lenora Chaney, who, as previously mentioned, was receiving payment on her husband’s behalf but who passed away earlier this year.

Of the 95, 39 were wrongfully convicted in Dallas County, accounting for over $56 million in lump-sum payments and $294,000 in monthly annuity payments. At least 19 of these convictions – 18 of which involved Black men – happened between 1980 and 1987 under District Attorney Henry Wade. Wade, who passed away in 2001, never lost a case he personally tried.

Wade is best known as the defendant in the 1973 landmark Roe vs. Wade case and for securing a later-overturned murder conviction against Jack Ruby.

According to NBC News, as of 2008 (before the Tim Cole Act became law), 19 additional convictions tied to Wade had been overturned. Questions remain about hundreds of other cases.

Who Was Tim Cole?

Ten years after Cole’s death, a Texas judge exonerated him posthumously, and Cole became a symbol of the flaws in the criminal justice system, particularly regarding wrongful convictions and racial biases. Texas Gov. Rick Perry pardoned Cole on March 1, 2010. After the Tim Cole Act was signed into law, state records show Cole’s family received a lump sum payment of $1,060,000

In addition to the lump-sum payments and monthly annuities, it established the Timothy Cole Advisory Panel on Wrongful Convictions to study the prevention of wrongful convictions across the state.

Statistics: Compensation by State

Eight states and Washington D.C. compensate inmates more than $50,000 for each year they were wrongfully incarcerated:

| State | Exoneree compensation |

| Washington, DC | $200,000 |

| Nevada | 1-10 years: $50,000 per year 1-20 years: $75,000 per year 21 or more years = $100,000 per year |

| Texas | $80,000 |

| Colorado | $70,000 |

| Kansas | $65,000 |

| Ohio | $56,752.361 |

| California | $51,110 |

| Connecticut | $49,314-$131,506 |

| Vermont | $30,000-$60,000 |

Currently, 12 states have no compensation statutes in place for individuals who have been wrongfully convicted. The states are Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, New Mexico, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming.